Everyday India in Snapshots

Ananya Saraf

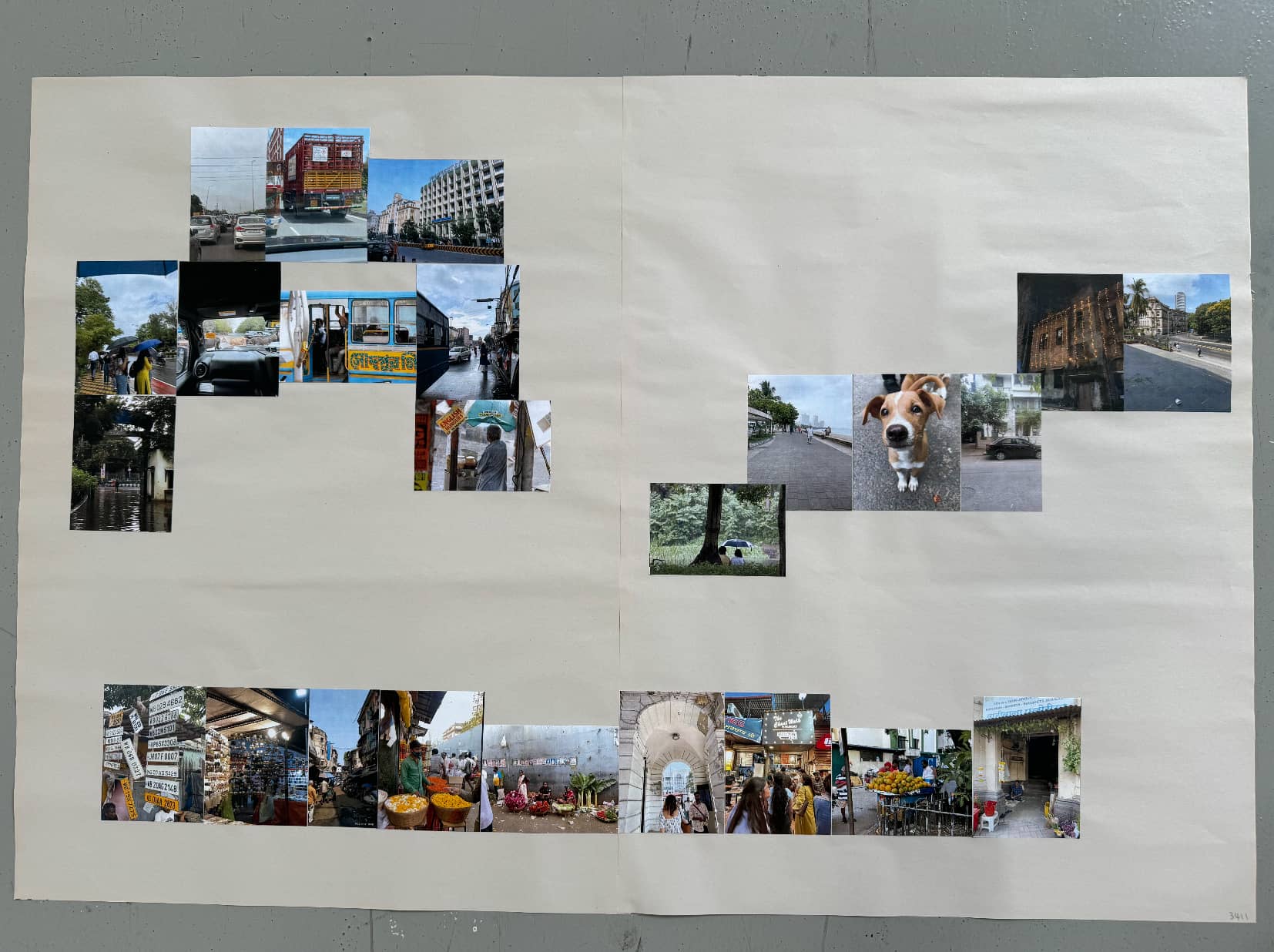

In the immensely rich history of Indian photography, Ananya observes a tension between India photographed by Indians versus the rest of the world. A century and a half from the arrival of the camera in the subcontinent today, in an age of mass-photography, every Indian individual with a mobile camera becomes a contributor to this visual vocabulary created by photography. Everyday India in Snapshots explores narratives, identities and conventions in snapshots of India by everyday Indians, through a process of collection, making, arranging and rearranging of a visual material largely understudied.

How did you start your explorations in these snapshots?

Through my entire project, I surveyed 500 photographs from everyday people in India — people who do

not consider themselves professional photographers or who just capture for the sake of capturing

like memory-making or documentation. With these 500 photos, I wanted to look at what value they can

provide in terms of information, identities, themes. And what I’ve done

is sequencing, arranging, rearranging, cutting, and seeing what conventions, themes, narratives,

overlaps and outliers I can. So again, my project does not have an end goal and neither does it give

me any big insights about everyday India, but it gives me opportunities and starting points of

proving that yes, snapshot photos have a lot more value than we give them on a regular basis.

And what I’ve done

is sequencing, arranging, rearranging, cutting, and seeing what conventions, themes, narratives,

overlaps and outliers I can. So again, my project does not have an end goal and neither does it give

me any big insights about everyday India, but it gives me opportunities and starting points of

proving that yes, snapshot photos have a lot more value than we give them on a regular basis.

After making this realisation of the value in snapshot photography, what was your next step?

More than a realisation, my entire project was understanding and exploring

different ways. Not every way worked out. I did a few in terms of juxtapositions and narratives,

where if I place two images together, what can I get out of it?

Not every combination will give me something, but it provides

opportunities. Then there was at the physicality of snapshot photography, looking at it in a

three dimensional way. With this realisation, again, like I mentioned, I didn't have any insights,

but it proposes a method of research.

Not every combination will give me something, but it provides

opportunities. Then there was at the physicality of snapshot photography, looking at it in a

three dimensional way. With this realisation, again, like I mentioned, I didn't have any insights,

but it proposes a method of research.

So say if I am a product designer and I'm designing a product and I want to know how people see or use something, I could collect snapshot photographs relating to that theme or utility. Apply these methods of looking at those photographs and I would get very specific insights. So it's looking at snapshot photography as a method of research as something valuable. At the same time, the context itself (everyday India) is somewhat of an ongoing project. 500 photographs in the context of everyday India is too tiny to be able to get any insights. If I keep collecting over the years, I will start noticing a lot more and then I can narrow it down and I can get 10, 20 different topics I can talk about. So the methodology and process in this project is a lot more important than the insight for me.

Because you're looking at these images from a third person's view, was there anything that kind of made you notice about the way that they take photographs and how they value these photographs?

My survey was in two parts. One was with friends and family so I knew some of the context that they took the photos in. And one was with a more socially disconnected group. Some friends that I know who have that aesthetic eye, from being on social media, have a lot more sensibility of looking at perspectives, horizons, and they take a lot more scenic photos. Then there are people who will click more cliched photographs, like holding a mug, or more horizons, or mangoes, something very specific.

I even got some photos which are blurry. You can tell that it's been taken by mistake. So it brings up questions that, oh, it's still in their gallery and they remembered to send it to me. They have tens of thousands of photos in their gallery and I asked them for 25 to 30. So they remembered that one and they sent it to me. That is also another way of questioning: why are you keeping it? What can it tell me about you?

See Kau Faham Bahasa Tak?, Nusantara Bergaul, and Teh Tubruk: A Visual Feast for Teatime

See 寄节 (jì jié), more than just chicken rice, and Souvenir City

See Characraft, and Exhibitions beyond Immersive Augmented Reality

See Invisible City